10 minutes

The emergency phone in blood transfusion shrieked. It’s a loud, piercing sound that made your heart race, no matter whether you were napping in a spare few minutes on a night shift, or already running around trying to accomplish the 47, and ever-increasing things on your to-do list. The shrill probably also raised the dead in the mortuary, somewhere in another part of the hospital. It was switchboard calling. “Hi, I have overnight intensive recovery on the line,” said the voice.

“Go ahead,” I replied. “Put them through.” When switchboard calls this phone, there’s no time for pleasantries.

There was a click, and the calmness of the operator was replaced by chaos. “Hi, it’s OIR. Could I start a code red please? We have a patient on the ward who’s crashed and have had to open them up.”

A code red is a rapid response code. No matter what you were doing, you put it down (or drop it in my clumsy case) and direct all attention to the code red. In transfusion, a code red initiates the major haemorrhage protocol. There are many definitions of what volume of blood loss constitutes a major haemorrhage, but these are all very academic and arbitrary in my opinion as this can only be best determined retrospectively. One states it is the total loss of blood volume within 24 hours, another, the loss of 50% in 3 hours, or finally the last one indicates a loss of 150mL/minute. For comparison 150mL/per minute would take a little over 2 minutes to empty out a standard sized coke can. It takes me at least 5minutes to drink one, and longer if it’s been in the fridge. I always get that funny feeling in the nose. The most useful arbitrary definition of a major haemorrhage in an acute setting is the British Society of Haematology’s as any bleeding that leads to a heart rate more than 110 beats/min and or systolic blood pressure less than 90mmHb. As blood is lost, there is less of it to carry oxygen around the body and so the heart works harder and faster, beating quicker. Alongside all the other complications, exhaustion and hypovolemic shock would occur. John C. Warren and Samuel Gross, two American surgeons from the 1800s defined shock as being a “momentary pause in the act of death”.

I got that funny feeling in the nose, this time due to an impending sneeze. I tried my best to ignore it and reach for the code red telephone request form, glanced over to the bottom right corner of the computer screen, looked at the time and noted it down at the top. 19:25, the clock starts ticking. 10 minutes, from phone call to products at the bed side. Tick. Tock.

In 2010, the National Patient Safety Agency highlighted that one of the repeat causes for morbidity and mortality was the delay in blood provision. In the UK, approximately 80% of deaths in the operating theatre and approximately 40% in trauma situations are due to haemorrhage. There are a multitude of changes that occur in the human body in response to a major bleed. As the blood volume decreases, the body cleverly shuts off supply to non-vital areas and diverts what’s left to the vital organs. If those other areas are deprived of oxygen for too long, the blood vessels therein release inflammatory chemicals which can lead to secondary organ damage associated with multiple-organ failure (MOF) and death. This effect on the blood vessels is also thought to hinder the blood’s ability to clot. In trauma situations this is referred to as acute traumatic coagulopathy. Initially the patient is unable to stop bleeding, which is subsequently compensated by hypercoagulation, increasing the risk of thrombosis or a clot blocking a vein or artery.

“Can I take the patient details?” I asked. There were voices in the background, I can barely hear what she is saying. Rushing. Tick. Tock. I was halfway through doing a full serological crossmatch for one of the patients with sickle cell disease who was coming for an exchange transfusion. It had been a quiet evening so far. Damn it, did I just say the cursed Q word? Another side-eye glance at the time told me there were 8 minutes left. My haematology partner came to help. She had been trying to call a GP about a critically low haemoglobin result for a patient, but it was late and no-one was around to take the call. She said that she’d try to call the result to 111 afterwards.

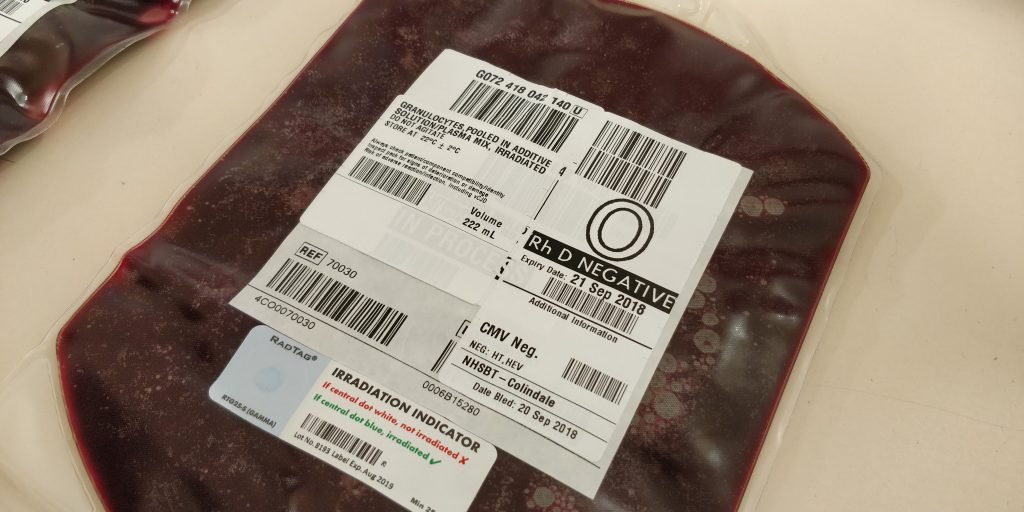

“Can you grab me 6 B Pos red cells and the emergency FFP please?” The bleep went off. I had no time to answer it. 7 minutes. I grabbed a pool of platelets from the agitator in which they’re stored and issued them on the computer to the patient. The medical laboratory assistant tells me the analysers haven’t been transmitting results for some time and the work file of outstanding tests is getting longer and longer. They were almost ready to go home. I made a mental note and added it to my list of things to deal with later if I have time or hand over to the night shift when they arrive at 20:00.

Birth centre bleeped again. “I’m one of the midwives on the Birth centre. I sent a sample to you for a group and screen but it’s been rejected. Can you tell me what’s wrong?” she asked.

I don’t have the time to be dealing with that right now. “I’ll call you back,” I say, “we’re currently in the middle of a code red.” She understood and hung up.

The porter arrived. When a code red is initiated, in the interest of time, switchboard kindly inform a few people. They call the blood transfusion laboratory and get us in touch with the person asking for the code red. They bleep the haematology registrar on call and inform them, so that they can oversee and provide assistance to the team. They also let the coagulation laboratory know, who then come to the transfusion lab and ask for the details of the patient having the haemorrhage, so that they can keep an eye out for the samples and process them urgently.

6 minutes to go. The red cells and the platelets had been issued and my colleague had them packed in separate transport boxes. I was printing the transfusion tags for the FFP when the printer jammed. This was the back-up printer as the other printer’s alignment was off and so temporarily out of use. Ensue me switching to French for a few seconds. I popped open the hood and tried to remove the jam. My colleague was ready to reprint the labels, her finger hovering over the mouse waiting for my signal. Four of the tags wrapped around the roller at the mouth of the printer. The sharp cutter at the end that’s used for tearing the labels tore my glove instead. Luckily my skin was still intact, only a little sore. Pulling the labels out is a balancing act. You pull too hard and they rip, meaning it takes time to get a good grip on what’s left. You pull too slow and your conscience tells you to hurry up because there’s a patient bleeding waiting for the blood and products. So you have to do a Goldilocks, not too quickly and neither too slowly. Somewhere in between. Just right. I fed a fresh label through the mouth, clamped it shut and closed the lid. It took me more than a minute to do it.

“Okay, try again.” She clicks. The clock ticks.

I grabbed another transport box and throw in the units as she tagged, and scanned each label followed by the unit it is tagged onto to make sure everything is labelled correctly.

“Okay, these are going to OIR bed 6, please” I said to the porter, who pounces. It’s his turn to carry the baton. He nodded. He knows what he has to do. He’s got 4 minutes to do it. “Thanks for the help,” I said. There were two bags of cryoprecipitate in the thawers. There was still another half an hour or so to defrost. My colleague went back to haematology to get on with the outstanding blood films and the malaria parasite screen that has arrived and needed setting up.

I called Birth Centre. “So the patient’s DOB was incorrect. You’d written the year as 2019. She’s 35, not 5 months old. That’s why it was cancelled.”

“But I wrote it myself,” the midwife protested.

“You’re more than welcome to come and see for yourself, you know where we are.” She never came.

I still had that crossmatch to finish and the analyser transmission issue to deal with. The cardiac SHO called as he does religiously, every day at the same time to make sure blood is ready or ordered for the surgeries in the morning. He has a list and it’s going to take some time checking every patient.

Tick tock. It never stops.

It’s a well-oiled process, and as long as everyone follows their training, the situation can be handled smoothly. Communication is key. I once checked my smartwatch after a code-red and noticed that shortly after the phone rang, my heart rate jumped to 108. Maybe I was having an internal bleed. Or more likely, I just needed to get out and do some running. Preferably on a regular basis.

Privacy Policy | Refund & Return Policy | Only Cells LTD © 2025

8 Comments

Fabulous read my friend. A Trust learning point ensure that the Specialists that need to check availability of E-I availability or pre-surgery cross matches have their own log in, with training! Bank Manager Transfusion LIMS is superb for this “Ward” look-up. Would sort your midwife’s too ( 2 less calls to deal with, regularly).

Look forward to the next Chapter.

I really enjoyed reading this Anas and could truly relate! I look forward to seeing more of these posts 🙂

Thanks Tahmina. Glad you enjoyed reliving the stress of a MHP!

A very good account of the transfusion laboratory. Well done!

Thanks Paul! Glad you enjoyed it.

wow, exactly gone through the same scenario, remember running around like crazy, phone ringing, bleep going, porter waiting. 🥰 well done. good read🌺

Thanks for reading and for the feedback! I’m sure it’s a situation many transfusion biomedical scientists can relate to.

Thank you for a great read, Anas! It seems life in a busy Transfusion Laboratory is comparable to the script scenario – familiar chain of events and situations 😀